Ronald Reagan Institute

Evaluating the Biden Administration’s National Defense Strategy and Budget | By Mackenzie Eaglen

By Mackenzie Eaglen

Prioritizing is hard, but necessary. Policymakers of all stripes have been unable to do so consistently with respect to American foreign and defense policy for decades. The result is a military sleepwalking into strategic insolvency.1 While elevating the threat of China, as the 2018 defense strategy did, is smart, the most recent National Defense Strategy (NDS) is additive in nature—expanding mission scale and scope without corresponding manpower, concepts, and dollars.2 The result is another force planning construct that does not adequately account for the full breadth of what the nation asks the armed forces to do in war or peace. Current and planned defense budgets will not be sufficient to carry out the actual requirements of U.S. strategy.

Rectifying this mismatch will require both more investment and fewer demands on U.S. forces.3 Defense planning should rest on realistic assumptions about the inability of policymakers to make hard choices and a cautious appreciation for the observed historical and expected future requirements of America’s armed forces.

Bureaucracy’s Gonna Bureaucracy

The defense budget is eye-wateringly large. So why can’t it resource the strategy to compete or win if necessary? Because much of the defense budget itself is fenced off for must-pay bills, leaving precious little trade space for any leader seeking to impose change on the largest bureaucracy on the planet. As former Pentagon Comptroller David Norquist has highlighted, the Department only shifts 10 to 15 percent of its budget any year given the many inherent fixed costs of running a three-million-person enterprise. From there, Congress only tinkers with a fraction (about five percent).

The result is a very small percentage of the defense budget left that is flexible enough to pursue change. Add in annual defense inflation, which tends to outpace wider national trends by two to eight percent depending on account, enterprise-wide depreciation,4 and all the non-defense spending inside the defense budget,5 and the stark reality is spending more to get less.

Between two-thirds and three-quarters of the entire defense budget is preordained and essentially spent before policymakers can begin choosing how to advance their strategy. By virtue of understanding the fixed-costs associated with defense, one can begin to understand the few truly strategic choices that are left to make and the impact of those strategic—or more often non-strategic—investments over which they do have control.

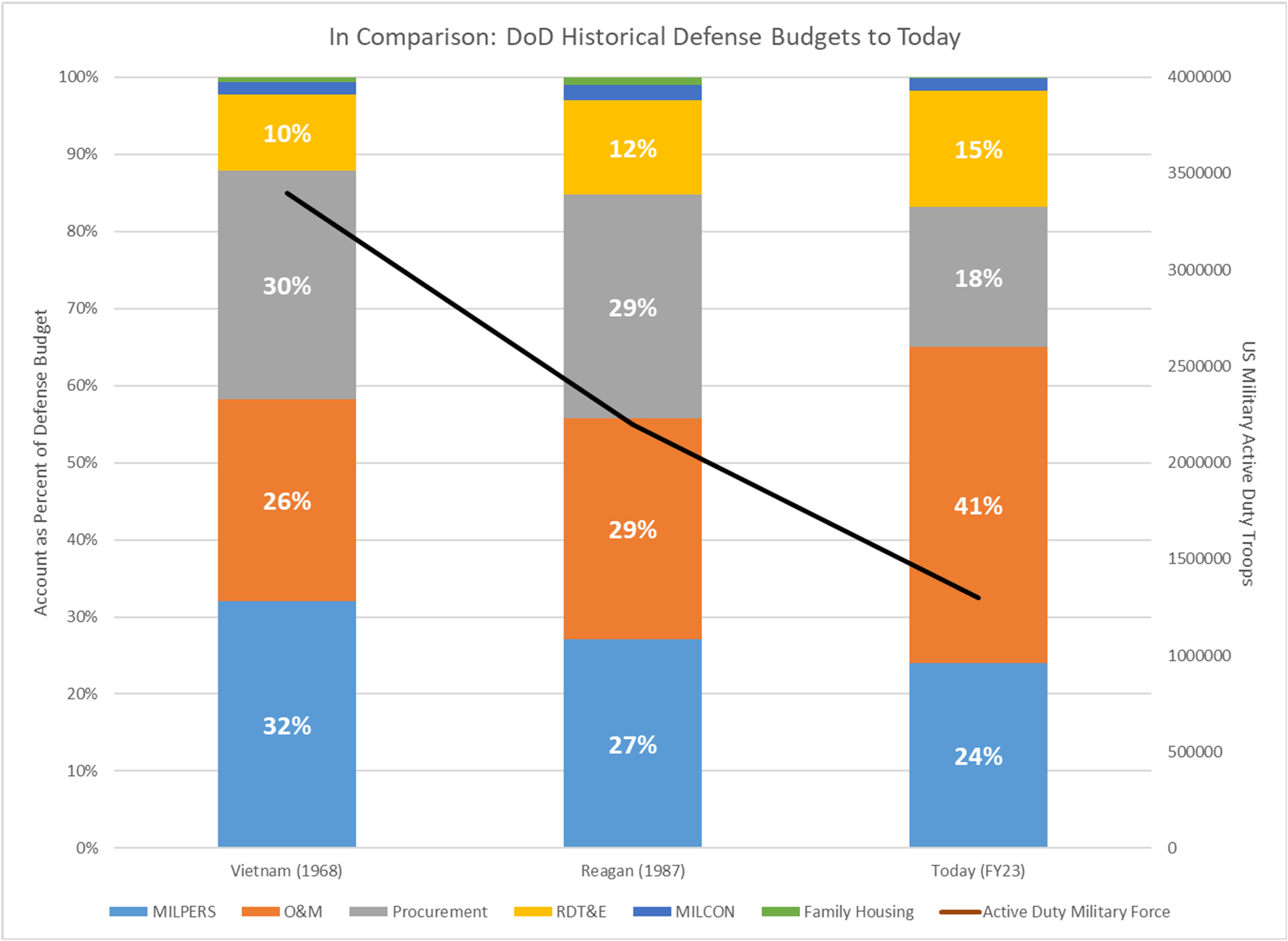

Specifically, as MajGen Arnold Punaro, USMC (Ret.) outlines in his latest book, taxpayers are currently spending more on defense in constant dollars than at the peak of the Reagan buildup—but for an active-duty military that is half the size and significantly busier.6 The U.S. Navy, for example, has averaged 100 ships forward for the past 30 years. Over that same timeframe, the fleet has shrunk from not quite 600 ships to 285. Yet today, the Navy has 128 ships at sea—a stunning number given the overall shrinkage of the force and absence of major conflict or hostilities for U.S. forces.

A Pentagon on Auto-Pay Limits Purchasing Power

Each year the Pentagon orders up a defense budget, just like one would a pizza—telling the cooks (Congress) what they need to fulfill their hunger and the right ingredients for their appetite. Now imagine having that eight-slice pizza for your party delivered but only being able to eat 1.75 of those slices. This is the reality that DoD and Congress are facing—what they want and need is eaten up before they get a chance. The defense budget’s fenced and fixed costs are only growing—essentially on autopilot even when action is taken to arrest the rate of growth. Like any large organization, the largest cost on the Defense Department balance sheet is for people. Of the $720 billion spent by the Pentagon in 2021, $300 billion (or 41 percent) was spent on pay and benefits like healthcare. Military personnel costs specifically (not including the 750,000+ federal defense civilians) have more than doubled in the last 70 years after adjusting for inflation, according to Seamus Daniels of the Center for Strategic and International Studies.7 Staying competitive with the private sector and offering generous compensation packages given operations tempo means the “mandatory” spending bills get larger every year—whether the overall defense budget grows or not. Cutting the size of the active-duty force slows this rate of growth but does not reduce it—a shocking fact to many members of the Joint Chiefs who have traded away permanent capability in the hopes of reinvestment, only to find none.

Beyond rising costs for a shrinking force, the other half of the fact-of-life expenses—and also alarmingly disproportionate—are maintenance and sustainment costs. Operations and management (O&M) expenditures without civilian salaries or healthcare comprise 22 percent of spending, which is another near-quarter of the defense budget that is mostly locked-in, focused on sustaining the force with little flexibility for redesign. As the force gets older, it gets more expensive. Older equipment costs more to keep in service than buying new outright over the long term. This further squeezes money available for next-generation technologies and systems.

Lost in this vicious cycle of age and extended use is the ability to capture innovation and better performance, new energy efficiency and power generation, and adaptability of more advanced equipment. With geriatric fleet lives constantly extended in order to prioritize future technology over replacing outdated inventories today, these bills will continue to rise faster than the overall topline.

Both people and maintenance costs “consistently rise faster than the rate of inflation.”8 Once under-budgeted inflation is paid, the bulk of annual topline growth (if there is any at all) keeps the Pentagon on cruise control—only maintaining existing force structure. The Trump Administration’s buildup spending nearly $100 billion above the previous administration’s plans, for example, yielded precious little in the way of new or more equipment. In fact, President Trump asked for the same number of new construction ships as President Obama had in his outyear plans—even though there was significantly more money available. That money went to mostly plug holes and repair the frayed foundation from the Budget Control Act era. The “Trump bump buildup” went to repair not to rebuild the U.S. military.

This is because of the military’s enterprise-wide depreciation—a gradual capturing of investments by fact-of-life accounts that seem to ignore logic.

The value of the Defense Department dollar, and therefore its buying power, diminishes each year under the weight of these accounts. Therefore, with a plurality of the defense budget linked to pre-paid bills and utilities that require yearly increases above inflation just to keep the organization churning, little is left for the actual strategic choices that should guide the military through great power competition as mandated by two consecutive National Defense Strategies.

Defense depreciation is a real but unrecognized phenomenon of the declining value of the military’s inventory of combat capabilities over time. This depreciation imposes hefty but silent costs on the Defense Department. Just as a car’s value goes down the day it drives off the lot, a military platform begins to depreciate when it is fielded. The longer it remains in the fleet, the more wear and tear it experiences, and the costlier it becomes to operate. As adversaries introduce new platforms and technologies of their own, the relative capability of the warplane is likely to decline—that is, unless more money is spent to upgrade its sensors, weapons, or other enabling technologies so it can stay ahead of the threat.

Depreciation by comparison occurs when a system’s value declines as a result of a competitor’s innovation, speed and scalability. As China surges ahead of the United States in hypersonic missile development and capability, the military is scrambling to quickly mobilize some form of hypersonic missile integration. In a House Armed Services Committee (HASC) hearing on the Air Force’s budget, it was revealed that arming the F-15EX fighter with hypersonic cruise missiles would be the only hypersonic capability in which the United States would have advantage over China.9 This means a fourth-generation fighter, of which the Air Force is reducing overall procurement, would again be subject to major operations and maintenance investments related to the modified capabilities.

Money & Mobility Making Defense Bills Magnets

One challenge in addressing these high percentages of fixed costs is that many of these sums are marbled into various and often-unrelated accounts. The obfuscation of where the dollars go makes it harder to determine how well they are being spent—to include on the NDS.

However, there is no doubt that the barnacles of earmarks and bureaucracy have built up and calcified within the defense budget over decades. As Elaine McCusker has said, the Pentagon spends more on the Defense Health Program than on new ships.10 It spends almost $10 billion more on Medicare than on new tactical vehicles.11 It spends more on environmental restoration and running schools than on microelectronics and space launch combined.12

The former acting Pentagon Chief Financial Officer (CFO) continues,

DOD currently funds activities more appropriate to other departments. In FY 2020, DOD had a budget of more than $1.5 billion for medical technology development, including autism and breast, ovarian and prostate cancer research. In parallel, the National Institutes of Health, where such federal efforts should be supported, had a total budget of more than $250 billion, within which $17.7 billion was reserved for conditions and diseases DOD also funded.

Defense budgets also include money (albeit minor amounts) for education grants for state and local entities, law enforcement support, and blankets for the homeless. Not really core DOD competencies.13

From Congress using the largesse of defense to fund projects that are important but unrelated to deterring war to running schools, grocery chains, hospitals, patrolling the southern border, and now helping mitigate climate change, so much of what gets lumped into “defense spending” is not yielding tangible combat power that deters or defends.

Unlike the Reagan buildup where dollars were concentrated in procurement and purchasing of new hardware, the Biden budget has made procurement its billpayer for extraneous missions. The Pentagon’s unhealthy ratios of building new equipment to researching next-generation technology are only worsening. The Defense Department has again requested record funding for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) in 2023. But without the procurement dollars to take R&D efforts from the laboratories into the hands of warfighters, these are roads to nowhere.

Urgency is largely absent in this strategy and among the leadership executing it, as evidenced by their long-term, reduced-force financing plan. Meanwhile, military planners across the Armed Services are suffering the result and pleading the case.14 The first-ever Air Force software officer Nicolas Chaillan resigned last fall, citing lack of budgetary support for joint all-domain command and control (JADC2) and the inability to act with agility to “enable the delivery of timely capabilities at the pace of relevance.” Former vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. John Hyten warned, “it’s going to take us 10 to 15 years to modernize 400 [intercontinental ballistic missile] silos that already exist.” However, “China is basically building almost that many overnight.”15 And Marine Corps deputy commandant for combat development and integration Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl reiterated the sentiment of many other leaders stating plainly: “If anybody thinks we are moving fast enough, you’re crazy.” The funding applications proposed by this department and strategy fail to address the most urgent causes—US combat strength and capability in the next five years.

In the coming year, the Pentagon would spend only $1.12 in procurement for every $1.00 spent on RDT&E. This is down 7 percent from FY22, and a stark decrease from the 1980s modernization-era, when the Department spent an average of $2.74 on procurement for every $1.00 on RDT&E. The percentage of the budget devoted to future bets (R&D) does speak to the Department’s deep and shortsighted commitment to the idea that America’s hardest threats are a decade out. Yet this misguided belief that threats will pause and wait until we’re ready to defeat them only invites that aggression earlier given our simultaneous declining conventional and nuclear deterrence.

Of the one-third or so portion of the defense budget that is seemingly spendable (aka, left on DoD’s debit card), the Biden Administration only requested 18 percent—or $145 billion—for direct procurement. Once Congress gets a turn, less than 15 percent of funds can actually be invested strategically toward the pacing threat and a strategy of denial.16

Mortgaging the present in the hopes of buying the future did not work for the Air Force in the 2008-2011 timeframe, nor will it work for the Marine Corps and other services today. The Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 permanently gives away capability, capacity, and manpower now to free up funds to invest in modernization and technology tomorrow.17 Moreover, whether or not one renders the plan appropriate for the challenges facing the United States, the optimistic approach has no plan B. After two consecutive budgets that failed to fully fund inflation and fact-of-life costs, Commandant of the Marine Corps General David Berger has been forced to shed headquarters staffing by 15 percent, cut end strength and legacy systems, and still after all that is left with nothing to fund new programs and projects that advance his vision. He stated last fall that “we have wrung just about everything we can out of the Marine Corps internally. We are at the limits of what I can do.”18 The service divestments yielded not one penny for investments.

In the latest budget request for 2023, the US Navy is not just proposing a strategy of “divest to invest” according to a longtime Washington observer of defense issues. The sea service, in the case of at least one of the modernized Aegis cruisers and some of the more recently procured Littoral Combat Ships, is in effect proposing a strategy of “invest-to-divest.”

The Strategy-Resource Conflict, Not Compliment

Let this and the other examples above serve as case studies for how the 2022 National Defense Strategy takes form and comes to fruition, or not. Disguise a declining defense budget under bigger numbers but palpably reduced buying power, squeeze people and ask the smaller force to do more with less, and weaken conventional deterrence. Integrated deterrence by disintegrating the services—it is easier to become whole when you have fewer pieces to the puzzle.

Former Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work said it best, “The United States cannot maintain force structure on flat defense budgets.”19 This is to say nothing of doing new, more, and better with the defense budget. This Administration is strategic about how they are cutting massive amounts of capacity under the guise of growth. Few understand just how much of the defense budget is on the available “debit card” for change. But the Administration does, and they intentionally allow defense depreciation to spread like wildfire throughout the Department.

The new defense strategy incorporates the most significant themes of the 2018 NDS, which is helpful, but it does so by taking the risky gamble of capacity and capability gaps in the near and medium term while expanding the military’s missions. The rampant disease of fixed-costs marbled within the budget will hold back any team that is not full of frothy pitbulls. The first step toward steering this ocean liner of a bureaucracy in a smarter direction toward deterring China is to see the spending handcuffs as they exist and increase funds above inflation where strategy demands—not just where costs are fixed. The 2022 NDS may reiterate familiar points, but the associated budget request is only masquerading as robust. In reality, the military will only continue to shrink and age under this program, and the promised vaunted future, if it ever arrives, will not be until after this team leaves office.20

Washington knew the “Terrible 20’s” were coming for a long time.21 But in recent decades, leaders have continuously deferred the hard choices to better phase our internal spending challenges of conventional and nuclear modernization simultaneously over a more agreeable timetable. In the meantime, our competitors have not only caught up but are now out-running us militarily in many ways. Now the United States is at risk of hastening the day Chinese Communist Party leaders conclude they can take Taiwan because in five or so years, we will have (potentially) fielded capability such that its chances of success might diminish. By advertising that we think it is better they move now because they will lose in the future, America may just be inviting the outcome we hope to avoid.

Rick Berger and Mackenzie Eaglen, “‘Hard Choices’ and Strategic Insolvency: Where the National Defense Strategy Falls Short,” War on the Rocks, May 16, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/05/hard-choices-and-strategic-insolvency-where-the-national-defense-strategy-falls-short/.

US Department of Defense, “Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy,” https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF.

Elbridge Colby, Mackenzie Eaglen, and Roger Zakheim, “How to Trim the Defense Budget Without Harming U.S. Security,” Foreign Policy, September 30, 2020,

Dustin Walker and Mackenzie Eaglen, “Inflation is the New Sequestration,” Defense One, April 1, 2022, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2022/04/inflation-new-sequestration/363879/

Elaine McCusker and Emily Coletta, “Is the U.S. Military Ready to Defend Taiwan?,” National Interest, February 6, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/us-military-ready-defend-taiwan-200295.

Arnold L. Punaro, The Ever-Shrinking Fighting Force (McLean, VA: Punaro Press, 2021).

Seamus Daniels, “Accounting for the Costs of Military Personnel,” War on the Rocks, September 22, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/09/accounting-for-the-costs-of-military-personnel/.

Robert Work, “Storm Clouds Ahead: Musings About the 2022 Defense Budget,” War on the Rocks, March 30, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/03/storm-clouds-ahead-musings-about-the-2022-defense-budget/.

Department of the Air Force Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Request, 117th Congress, (2022), https://armedservices.house.gov/hearings?ID=5E7CF224-5C81-4567-BCC3-D66F25DF6C75.

McCusker and Coletta, “Is the U.S. Military Ready to Defend Taiwan?,”; and Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer, United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2022 Budget Request: Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System, May 19, 2021, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2022/FY2022_Weapons.pdf.

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer, United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2022 Budget Request, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2022/FY2022_Budget_Request_Overview_Book.pdf.

Ibid.

Elaine McCusker, “Examining National Security as Part of the Entire Federal Budget,” RealClearDefense, November 10, 2020, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2020/11/10/examining_national_security_as_part_of_the_entire_federal_budget_583550.html.

Mackenzie Eaglen, “How the Ukraine Crisis Could Make the US Military Stronger,” 19FortyFive, February 28, 2022, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2022/02/how-the-ukraine-crisis-could-make-the-us-military-stronger/.

Mikayla Easley, “JUST IN: Hyten Says Pentagon Moving 'Unbelievably Slow' with Modernization,” National Defense Magazine (National Defense Industrial Association, September 13, 2021), https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2021/9/13/hyten-says-pentagon-is-moving-unbelievably-slow-in-defense-modernization.

Forum for American Leadership, “National Defense Strategy,” https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/1d008308-a2e8-48d3-ac4d-11267653d021/National%20Defense%20Strategy.pdf.

Mackenzie Eaglen and Thomas Spoehr, “What Does the Marine Corps’ Return to the Sea Mean for the Army?,” 19fortyfive, June 8, 2021, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2021/06/the-marine-corps-tax-on-the-u-s-army/.

Patricia Kime, “‘At the Limits of What I Can Do:’ Marine Corps Commandant Makes Plea for Funding,” Military.com, June 16, 2021, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/06/16/limits-of-what-i-can-do-marine-corps-commandant-makes-plea-funding.html.

Work, “Storm Clouds Ahead.”

Mackenzie Eaglen, “Defense Strategies and Priorities: Topline or Transformation?,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute, https://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan-institute/publications/defense-strategy-and-priorities-topline-or-transformation/.

Mackenzie Eaglen and Hallie Coyne, “The 2020s Tri-Service Modernization Crunch,” American Enterprise Institute, March 23, 2021, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/2020s-tri-service-modernization-crunch/.

Join Our Newsletter

Never miss an update.

Get the latest news, events, publications, and more from the Reagan Institute delivered right to your inbox.